The statin hypothesis is that statins reduce cardiac risk more than can be explained by the reduction in LDL cholesterol. That hypothesis has been overturned by a new study.

The consensus of mainstream medicine is that a high blood level of LDL cholesterol is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease and that lowering high levels can help with prevention and treatment. Statins have been proven effective for lowering cholesterol levels and for decreasing cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. I recently wrote about the new guidelines for statin therapy.

Currently half of American men between the ages of 65 and 74 are taking statins, and 71 percent of adults with heart disease and 54 percent of adults with high cholesterol take a cholesterol-lowering drug.

There is still a fringe group of a few maverick “cholesterol skeptics” who think lowering cholesterol is useless or counterproductive, but the evidence shows they are wrong.

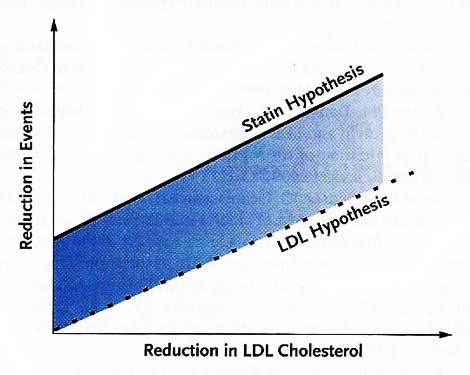

Statins are beneficial, but some have questioned whether their benefits are due to their ability to lower cholesterol or to their anti-inflammatory effects, or both. There are two competing hypotheses, the LDL hypothesis and the statin hypothesis. A new study in The New England Journal of Medicine sheds some light on that controversy and tips the balance in favor of the LDL hypothesis.

The LDL hypothesis assumes that lowering LDL by any means will improve outcomes. It is supported by a lot of evidence. In the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) study, a meta-analysis of studies involving over 90,000 subjects, they found that a reduction of 1 mmol per liter reduced the annual incidence of cardiovascular events by a fifth.

The statin hypothesis is that the improved outcomes seen with statins are due to other biologic effects unrelated to their cholesterol-lowering ability, in particular to their anti-inflammatory effects. There is also some supporting evidence for that hypothesis, such as the JUPITER trial, which showed that patients with low levels of LDL cholesterol but high levels of the inflammatory marker CRP benefited from taking statins. Previous studies showed no difference when other cholesterol-lowering drugs were added to statins.

The new statin study

The IMPROVE-IT trial was a large, well-designed, double-blind, randomized trial involving 18,144 patients over age 50 who had been hospitalized within the previous 10 days for a heart attack or high-risk unstable angina. Both groups got 40 mg of simvastatin; one group also got 10 mg of ezetimibe, a drug that lowers cholesterol by a different mechanism, reducing intestinal absorption. The combined group had significantly lower LDL cholesterol levels (53.2 mg vs. 69.9 mg) as well as significantly lower triglycerides, HDL, apolipoprotein B, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. The combined group also had significantly fewer cardiovascular events.

The absolute benefit was modest, with only a two percentage point difference in major cardiovascular events. There was no difference in all-cause death rates, adverse effects, or cancer. There was a high drop-out rate: 7% a year and 42% overall.

The event rate reduction was exactly what was predicted by the CTT analysis. An accompanying editorial concluded:

Overall, IMPROVE-IT provides us with important information on the value of lowering LDL cholesterol levels, regardless of the agent used. These data help emphasize the primacy of LDL cholesterol lowering as a strategy to prevent coronary heart disease. Perhaps the LDL hypothesis should now be considered the “LDL principle.”

Other new cholesterol-lowering drugs

PCSK9 inhibitors have been in the news. They are monoclonal antibodies that target and inactivate a specific protein in the liver (proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin). In three recent trials reported in the NEJM, they lowered LDL dramatically, to the lowest levels ever seen in a lipid-lowering trial, and patients were 50% less likely to have a heart attack or stroke or develop heart failure over the one-year period of the trial.

But they are not yet on the market, and the news is not all good. They must be injected every 2-4 weeks, they may be priced at $7,000 to $12,000 for a year’s treatment, and they may cause neurocognitive side effects. They might become a viable option if only for selected high-risk patients who are unable to take statins or whose response to statins is inadequate. Time will tell.

Lower LDL cholesterol any way you can

For patients at high risk of cardiovascular events, current evidence supports the strategy of reducing LDL cholesterol levels. The initial approach involves reducing other modifiable risk factors as much as possible (smoking cessation, blood pressure control, healthy diet, weight loss, exercise, etc.). If risk remains high, the next step is statin therapy. If statins don’t reduce LDL cholesterol sufficiently, the addition of another cholesterol-lowering medication may offer additional protection. If statins are not tolerated, other medications that lower cholesterol can be expected to reduce risk. The potential role of the new PCSK9 inhibitors is not yet clear.